A Deconstruction of Our Relationship with the English Language: An Exploration of Art, Elitism, And A Utopian Thought Experiment

March 11, 2022

Title: On the English Language, By Navarro Dodge (2/22/22)

As one who often enjoys sculling upon the waters of pretentious drivel, my writing and speech has consistently been criticized, as those who join me on the journey across this Styx of philosophy, avant-garde art, and criticism are often confused by my lack of consistent grammar. I often say things that are viewed by editors, peers, and teachers as not “dialogue of the articulate class.” However, I think that such verbal transgressions are, in fact, very important and should be more enthusiastically encouraged. I believe that opening our language to include slang, uses of grammar marked as “mistakes” such as misuse of the Oxford comma, and misuse of words such as literally to describe metaphors, is not only consistent with our history, but has led to amazing results in the arts. In fact, the evolution of our language could be a catalyst for the societal and systemic change we all crave. Overall, open language standards create cutting-edge art, and allow for social equality, which will lead to progressive change.

One caveat I will drop in is that this essay is not an attack on the amazing and talented English teachers who teach what I criticize. I must acknowledge that they are not to blame for the permeation and penetration of elitism in the way we interact with the English language. The elite run our society, and to function in this society, English teachers must teach us their method of speech so that we can be accepted by the rich that choose if we are successful in our adult life. Our enslavement to internalized elitism, which occurs in our English classes, is not only not unique to these classes but also necessary for our survival.

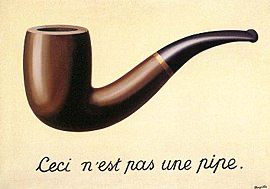

Before venturing into the political aspects of how the shifting of language affects societal change, I think we should begin in the place of my passion, that being art. Artists have constantly played with, morphed, and mutilated language and explored its place in our world and various cultures. The seminal piece of Surrealism, The Treachery of Images, by acclaimed surrealist René Magritte, is a perfect example. Magritte ingeniously plays with both the obvious message, that a picture of a pipe is not a true physical pipe, but also a double meaning: commenting on language. If we ignore the obvious message that the painting of the pipe is a painting and instead view the painting of the pipe as a physical pipe, the message at the base, “it is not a pipe,” still rings true. Pipes are not pipes; it is just that we have assigned them that term. Pipes are truly a mass of wood, metal, and ceramic. “Pipe” is merely either the sound of our vocal cords maneuvering our mouths or a series of lines. They are not the same thing. Thus, while the painting is most obviously commenting on our interpretation of images, it is also commenting on our interpretation of words to great effect. Through this new use of the English language, using it to name things not as they are, we now review the legitimacy of our language, we question why we assign certain sounds to certain things, what makes something something. It thus creates an amazing and provocative commentary on our societal constructs, all through not using our labels we created, similarly to how modern generations don’t use words like “irony” and “literally” in the ways they were originally intended to be used.

message at the base, “it is not a pipe,” still rings true. Pipes are not pipes; it is just that we have assigned them that term. Pipes are truly a mass of wood, metal, and ceramic. “Pipe” is merely either the sound of our vocal cords maneuvering our mouths or a series of lines. They are not the same thing. Thus, while the painting is most obviously commenting on our interpretation of images, it is also commenting on our interpretation of words to great effect. Through this new use of the English language, using it to name things not as they are, we now review the legitimacy of our language, we question why we assign certain sounds to certain things, what makes something something. It thus creates an amazing and provocative commentary on our societal constructs, all through not using our labels we created, similarly to how modern generations don’t use words like “irony” and “literally” in the ways they were originally intended to be used.

An art-form that more-commonly and famously breaks the conventions of language and grammar is poetry. My favorite of these poets changing the norms of the English language is E. E. Cummings. His disregard for the conventions of grammar and even poetry can be seen in many of his works. For example, in the poem “anyone lived in a pretty how town,” Cummings not only doesn’t capitalize the title within the confines of how all writers are taught to capitalize. He entirely changes the sentence structure to build this uncanny distortion, which while at first odd, creates a beautiful child-like flow. It creates a feeling almost invoking floatation that makes many readers move to his work to feel an escapism only Cummings can provide. The destruction of language and grammar extends to the verses which read extremely interestingly. For example he writes:

“when by now and tree by leaf

she laughed his joy she cried his grief

bird by snow and stir by still

anyone’s any was all to her” (Cummings 1940).

The writing of Cummings works as well as it does due to how it lets the reader interpret the emotion of each passage. With no punctuation, there is no forcing of importance nor exclamation. What is important to the reader will stand out, no need for Cummings to sway such a personal thing as interpretation of poetry. The poem also now has a unique flow. For example, the line “she laughed his joy she cried his grief”(Cummings 1940), would normally be written under the conventions of the English language “She laughed when he was joyful, she cried when he was grieving”. But E.E. Cummings does not do this, instead mashing together the joy and laughter and the crying and grief, eliminating the extra words which we normally add, creating a gorgeous sense of floatiness and playfulness. The placement of the nouns also creates a bounce in the rhythm of the reading. The atmosphere of spacey floatation provoked in the title can be seen here, yet again, as the lack of grammar and sentence structure creates an ocean of imagery, which forces readers to abandon rigid tactical maneuvering. The style allows the audience to mentally relax as they feel the beauty on the page. It is also similar to the ways my generation often misuse grammar, especially the Oxford comma.

The deconstruction of writing can be used to present new interpretations of our relationship with language. The deconstruction of writing can also be used to create an emotional atmosphere. And, it can be used to do both simultaneously, which can be seen with many different avant-garde playwrights. My favorite of these playwrights pushing and molding language is Mac Wellman. In his interview with Marc Robinson titled “Figure of Speech,” published in PAJ: A Journal of Performance Art, Wellman talks about his experience reading Mencken’s American Language and how it affected his play Terminal Hip. Wellman states,

“I’d come across the phrase in Mencken: ‘If I hadda been’ -which is bad language. There was another one-‘if I mighta could.’ It’s the kind of stuff that you’d hate if you thought about writing well every waking moment. These horrible statements are things you try to get out of your system. You just look at them and they make your skin crawl. But then I’d put them together-these two phrases-‘If I hadda been I mighta could’” (Robinson 44).

Wellman shows that by disregarding our conventions of speech, we can create unique surreal landscapes through nothing but language and can push the boundaries of art and what emotions our writing normally is able to provoke. As Wellman concludes, “This is something you cannot say in any European language I know, or even in English” (Robinson 44). As Wellman shows us, moving past the rules of speech can make us feel things never able to be felt within the restrictions taught in our English classrooms. Terminal Hip stands out in the cannon of the American avant-garde because of this. The barrage of contracted out-of-use phrases makes one feel a disorientation rarely experienced in our world of standardized language and grammar, let alone in theater. It leads to a play that is unique, as well as humorous, due to its inherent oddness, making it push the boundaries of theater even thirty-eight years after its publication. Like Magritte, it is an ingenious commentary on the nature of the English language—and similarly to Cummings, it is a work of art providing a unique flow and atmosphere which attracts audiences due to its ability to provoke mental escapism.

Overall, in art, abandoning the conventions of English is a fantastic way to create new experiences, unique atmospheres, and interesting commentary on our world. It can be used to create beautiful landscapes, frenetic, disorienting dreamscapes, and present different ways to view our world and the societal constructs we take for granted. If we encouraged students to play with their language like Cummings and Wellman, we can build more creative artists who can express themselves in the manic way our artistic minds really work.

While the changing of language seems to be, from my examples, a trope only of the avant-garde, the changing of language has been a staple of art, even in the highest of the mainstream. Over 1,700 words we use in daily life today have been attributed to the famous works of the 1500s playwright William Shakespeare. And while his creation of words is unlike my other examples, as it is not to create atmosphere (other than naturalism), nor to promote artistic commentary, it still is interesting and important as it presents us with a hypocrisy of our English education system, and thus an interesting quandary: why is it that while students are chastised for the creation of new words, we study the works of a writer who does the same? And that question leads us to an enlightening revelation, which reveals one of the pillars of the institution that is the rules of the English language; and that is elitism. Shakespeare was a man immensely venerated by the elite of his time. Queen Elizabeth was a good friend and admirer of his work, even creating a theater for him. Meanwhile, the new words made by those of lower socio-economic backgrounds are just marked as slang. Because the elite liked him, his “mutilations” of the English language are allowed, as it seems in our society, and thus education, the rich and elite create the rules of our culture, conventions. This is especially evident not from an art piece but the history of a slang term. “Ain’t” was originally a standard contraction of the phrase “am not” among the elite up until the 1800s, when the phrase eventually caught on with the poor as well, who wanted to appear high class. As more and more lower-class people began using the phrase, it lost favor with the elite, as it was now associated with those of the lower-class. And now, that stigma around the phrase continually permeates. This leads to my point: how opening up the rigid rules for the articulation of the English language can be the basis for political change.

Often those who are of lower socio-economic backgrounds, accented communities, and various regions speak differently than the elite class. Often they cannot afford education teaching them in “the ways of the elite” because education in these communities has become increasingly expensive due to the elites of our society making it so. In tandem with this is an education system that constantly tells us that those who speak differently, who use contractions of sayings, who have accents, who do not speak English in the way taught by rich-led education systems are not smart, and should not be taken seriously as their ideas, due to their articulation, will not have merit. It means that when those of different backgrounds, who are not of the elite-class speak out against oppression, they are judged on their speaking habits, and not their ideas, leading to their oppression continuing as the elite-class has secluded the resources we all need to better our communities. If we abandoned these notions of what makes speech “correct,” and did not judge others’ articulation, we would be able to build movements and organizations lead by marginalized peoples that actually address their problems and goals from the voices of those who the goals would benefit, instead of just hearing what those educated in the dialect of the elite think their problems and goals are. It would also encourage more marginalized people to voice their concerns as they would not be fearful of people judging them for their speech. Through this opening of language standards, we could listen to voices that come from the various regions, socio-economic backgrounds, accented communities without judgment of their articulation, which would allow marginalized voices to speak up against oppression and build truly representative movements that address their problems and goals.

Altogether, language is really a tool. A tool we have used for artistic expression, and for marginalization. A tool we can change for the better if we accept a more progressive approach towards how we use it. If we encourage students to be creative with how they maneuver English and grammar, we can create more amazing art that pushes the boundaries of what English can normally say to new heights. If we encourage students to be more accepting and less judgemental of different articulations, we can create change that helps all of us, and encourage students to speak up for themselves even if they are scared of having to conform to the rigid rules of the language. It also can be a force to take away power from the rich who force our society to behave the way it likes it to, morphing the language on our own limbs instead of letting the elite control us due to our internalized elitism they pushed onto us through our education systems. The opening up of the English language can also be a catalyst for change; making us realize if we can improve something which feels as fundamental as the rules of our language, we can push for the betterment of other fundamentals of our society, such as economic, governmental, and education systems. Overall, making our language standards more accessible, has made some of the most incredible art of the past century, and will build more representational movements creating progressive social change helping our marginalized communities.