Kathrine Sullivan has been teaching English at EHS for 19 years. The Hive reached out to Sullivan about her innovative grading procedure.

The Hive: Could you run through what your grading policy is?

Sullivan: So, I do not give grades on individual assignments. If you turn in an essay, I’m not going to put an A, B, C, or D on that. I’m going to give you feedback on that essay and in PowerSchool, on the comments, I will put in what were the skills that we were assessing – the quality of the hook, the clarity of the focus, analysis of evidence, and I’ll give you a 1234 in there so you it’s not like you don’t know how you did. You’re getting feedback, but you’re also not getting the ABCD.

Every assignment that goes into PowerSchool is worth one point. If you turn it in, you get the point. If you don’t, you don’t. If you’re looking at PowerSchool through most of the quarter it’ll give you an average, but that average doesn’t mean that’s what your grade is going to end up being. It’s just like you have turned in 100% of your work. If you have anything less than 100 in PowerSchool, that means there’s something missing and probably you can make it up, but not always.

At the end of each quarter and semester, students write a grade letter. In the beginning of the year they receive great descriptors: What does it mean to get an A? What is required for an A, a B, a C, or a D, or an F? Then the students write a letter saying, “This is what I believe I’ve earned and here’s why.” They reference the work that they’ve done and the growth that they’ve had. Even before they do that, we look at some sample letters so that they know what this should look like.

So let’s say a student earned a B for quarter three and they feel they’ve earned an A for quarter four. It is really “What do you think you deserve for what you have learned this semester?” and they have to make that call and defend that? When I read their letters I’ve already written down where I would put each student and in doing so I’m looking back on my notes over how they’ve done and how they’ve grown. They know what’s been coming in on time, what was late, and if there is anything missing. I determine where I would place that student and then I read their letter and there are times that they bring things up that I hadn’t thought about or they put something into context that I hadn’t considered. I often have students who I have written down as a B or C, and they’ll talk me into the B. Now maybe they want the A and don’t get it, but they’ve talked me into that B. I find for most students, we’re in the same ballpark or we’re very close.

The Hive: What is the history behind this grading system?

Sullivan: Like every teacher I’ve ever met, I hate grading. It’s not that I hate sitting down to grade, but it’s that I hate taking something that a student has put a lot of effort into and looking over it, slapping a number or a letter on it, and handing it back. What I’ve seen for decades is students looking at that A, that B that C and their face is crumbling.

If a kid’s not doing well, I hate having to say, “You tried really hard, but it’s still a C.” For a lot of students who think an A+ is the only acceptable grade, that C is devastating. I found that when students were getting that work back, every conversation we had was about the grade, not about the writing and not about the reading skills. They wanted to talk about what do I need to do to get an A, not what do I need to do to become a stronger writer, stronger reader? It was always about the grade and their frustration with grades often got in the way of learning. That was frustrating to me.

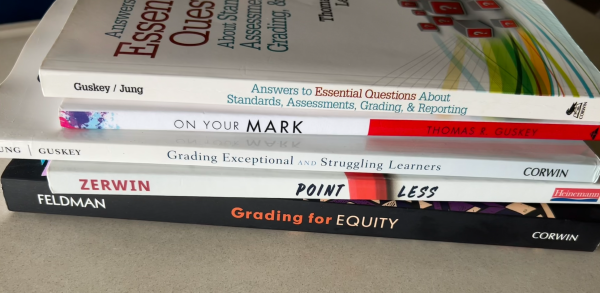

Over the years, at some point, the school brought in [Thomas] Guskey, who was talking about proficiency based assessments. That made sense to me. It connected all of these books I’ve read over the years.

But as a school, we’d also have administrators saying, “Don’t give zeros give 50s.” That didn’t make sense in my brain. I thought, “what do you mean give them a 50, they didn’t do anything. They did 0% of the work.”

Then when I read a book on grading for equity by Joe Feldman, he broke it down in a way that made sense to me. He’s like “We currently grade kids on a 100 point scale. The first 60 points are to describe their failure. We give 10 points to describe an A, 10 points to describe a B, 10 points to describe a C, 10 points to describe a D, 60 points to describe F.”

Mathematically, if you give a kid a 50, it will hurt their grade but their overall average is not doomed. They can come back from that. That was my first step: getting rid of zeros.

Then when I read Sarah Zerwin’s Point-less: An English Teacher’s Guide to More Meaningful Grading, she talked about how to get rid of grades altogether. I was already struggling with grading and questioning. It wasn’t working. It was getting in the way of my students’ growth. That set me on a journey of looking for mentors to help me come up with something that worked more for student learning versus impeding student growth.

Then when I read Sarah Zerwin’s Point-less: An English Teacher’s Guide to More Meaningful Grading, she talked about how to get rid of grades altogether. I was already struggling with grading and questioning. It wasn’t working. It was getting in the way of my students’ growth. That set me on a journey of looking for mentors to help me come up with something that worked more for student learning versus impeding student growth.

The Hive: How long have you been teaching in this style?

Sullivan: I’m about two or three years in. I have friends who are further on their journey than I am. I know there’s still things I want to do. I would love to have students identify very early on “What are the skills I’m focusing on?” and doing that weekly or bi-weekly. It becomes more regular that they’re taking ownership of tracking that growth and really getting to see what the specific skill they’re working on is, not just “What’s my English grade?”, but instead, “I am really working on analysis. of evidence. And here’s how I’m growing. And here’s how I’m tracking that myself.”

That’s a piece I haven’t completely figured out yet. I have been talking to another teacher who’s planning to go in this direction next year. I’m hoping that in working together, we can begin to come up with some systems that help streamline the process.

It’s still fairly new, but I wouldn’t go back. The writing I get from my students is so much stronger.

Does it work for every kid? I don’t think anything works for every kid. There’s no system that will be 100% for every single kid. But this takes some pressure off along the way.

The Hive: Do you think that students are still thinking about the grades even if it’s unspoken?

Sullivan: I think so. I think that we are conditioned by this system to focus on grades. I would love to erase that entirely and have kids only focus on learning. But no, I think that’s often still something that they are thinking about.

The Hive: Have you had students in the past few years come back after and give you commentary on your grading versus their junior/senior classes?

Sullivan: No, nobody’s come back specifically to talk about this. I mean, some of them will say, “Oh, yeah, the grade letter, I remember those.” But that’s as specific as I’ve heard.

I did hear from Ms. Chudy this year, who’s teaching AP Lang, said that when they were reading and responding to something there were some students in the class who recognized the example of what the article was talking about because they had been in my class.

The Hive: Do you think that a similar grading system would be applicable in a science or math class?

Sullivan: When I’ve talked in brief conversations with other teachers, they’ll sometimes talk about how frustrated they are with whatever they’re facing with grading. I know that frustration and when I explain what I do, they often say something along the lines of, “Oh my goodness, I wish we could do that.”

I think about how much time in a math class you’re sitting there trying to figure out the right answer. Well, what about that process of getting even a wrong answer should be graded? So you’ve got a math teacher trying to decide how many points to give for the process and which pieces did this student get really well on a problem, but do they all count equally?

If it makes sense for the way that the teacher’s brain works, I think this grading system can work, yes. If the teacher says “Here are the skills we’ve been working on, and to get an A, this is the progress you’ll need to show.” It’s about growth towards that skill.

The Hive: If you’re looking at semester two, and seeing that student did not do very well in semester one, but you see that they’ve gotten a lot better, are you taking that improvement into account when deciding their final grade?

Sullivan: Oh, absolutely. Let’s say semester one was a B and semester two is an A. I have my thoughts on what’s more recent, which is a better representation of where they are in a traditional system. They now have a B+ or an A-. I have the power to say “I think that’s an A” and that kid also is empowered to say, “I know I have grown when I look back to first semester and at the comments on my pieces. I wasn’t talking about my evidence at all and now I’m zooming in on key words, I’m talking about literary devices and I’ve grown.”

Not only are the kids saying “I’ve earned the A,” they can actually articulate what they’ve learned, which I think is really powerful. We don’t always know what we’ve learned in a class if we don’t stop and look back.

The Hive: How do pluses and minuses factor in?

Sullivan: That’s the exam. For me, that’s the exam. When students show up for my exam, I will already have in PowerSchool their semester grade? Then, if they rock the exam, you nail everything, I add a plus. If you bombed the exam, I add a minus. So, if you come in and you have a B, the worst thing that can happen if you try on the exam is that you walk out with a B-. If you come in with an A, the worst thing that’s going to happen is that you walk out with an A-.

This is honestly also true mathematically. If you’re doing numerical grades like that, 20% of your semester grade really is only the difference between an A+ and A-. But I think psychologically for a lot of students, there’s this fear of “I can go from an A+ to an F if I don’t do well on this exam.” Mathematically not true, but emotionally very true.

The Hive: Did you slowly work in this process? Or was it one entire switch?

Sullivan: When I switched I made the switch. There are elements that I’m shifting and growing in each year, like thinking about responsibilities to learning and referencing those periodically. I mean, I don’t know how I could have gone halfway.

I also send a letter home at the beginning of each course to parents explaining that this is what’s different here. So when you’re looking at PowerSchool, this is what you’ll see, this is what that means.

During the week leading up to the end of the quarter, I go through PowerSchool and I deactivate assignments so they can still see all of the assignments and the comments on them, but it removes that A+/100.

The Hive: When you initially did this, did you have to have conversations with the English team? Or was it something that you could just do individually?

Sullivan: I mean, I had conversations with people but it was also just something that I shifted to on my own.

The Hive: Is there anything else you want to add?

Sullivan: I think that grades are something that are very personal. If, as a teacher, you’re using a system that does not make sense to your brain and the way you think about things, it’s not going to work.

I don’t think taking this system and saying all teachers must do it is a solution, I think that’s a recipe for disaster. But, I think if a teacher is in that situation, like I was in, this is an avenue to explore. You have to be able to explain to your students how your system works.